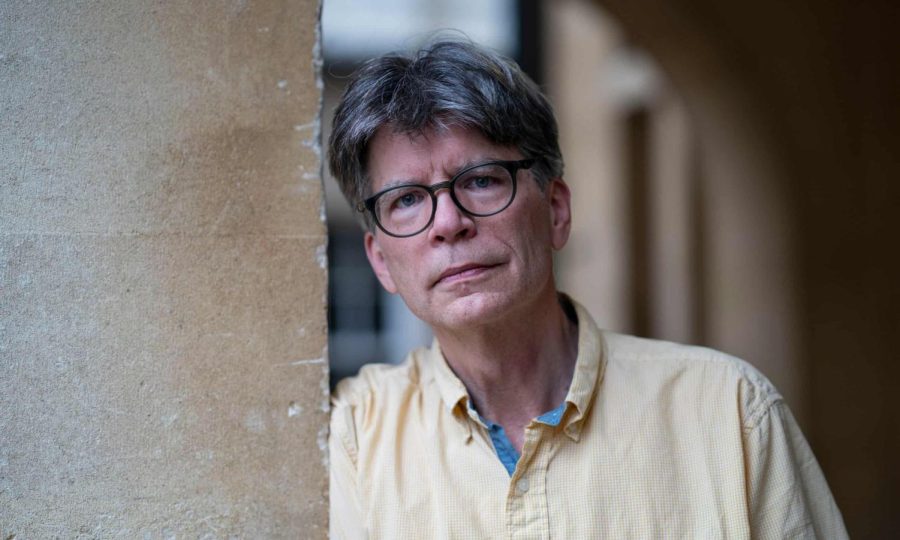

Ardon Shorr, OC ’09, graduated with degrees in Music Theory, Neuroscience, and Chemistry. He has since gone on to pursue a Ph.D. in Biology from Carnegie Mellon University and now teaches science writing and communication courses at Princeton University. His poem “Time Travel for Beginners” was recently named the winner of the 2023 Rattle Poetry Prize, which awards $15,000 for a single poem.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you get started with creative writing? Has it always been an interest?

One thing I loved about Oberlin is it always felt like we were encouraged to explore anything that we were interested in. I never felt like I had to limit myself. I remember being at a party once as a first-year. Everyone was doing the thing where they’re like, “What’s your major?” and someone said Physics. Someone else talking to them was like, “Is that it?” I thought it was such a funny encapsulation of how you expect people to be like, “Oh, yeah, I’m Physics and Trumpet Performance.” That was just a really common thing, that you didn’t just have to be in one box. And so I took the opportunity to explore widely. I think I’d always been interested in creative writing. I took a writing class with former Professor of Creative Writing Dan Chaon. I learned a lot. I started taking poetry in 2020 because I heard about a cool workshop that was happening with Megan Falley. She teaches a workshop called “Poems That Don’t Suck,” which I highly recommend. I wanted to write poetry so that I could propose to my partner in the form of a poem. I turned out to really fall in love with it. I wasn’t published all that much, but I felt like if I could just learn to see the world a little bit more sharply and take down information, that’s already worth it to go through life noticing more.

Science is typically thought of as very separate from creative writing. How do these different facets of your life connect?

I think science is the lens through which I found my voice in poetry. It gives me new things to start to notice. This poem that got published is about how when you look out into the stars, you’re limited by the speed of light into how far you see. So anytime you’re looking at the stars, we’re looking at the past. Stars could have already died by the time they reach us. Imagine if you could travel really far into space, you’d be able to look back on planet Earth and see our past, too. Just being able to think about those things is inspiration — I’m trying to work through the beauty of the world through a scientific perspective.

The other part of the story is that I got trained with a Ph.D. in Biology, but while I was at Carnegie Mellon, I started thinking about the way that Oberlin brings attention back to being in service to the world and thinking about bigger issues. I started to be really bothered that no one was training us how to talk about science outside the lab, talk about our work and why it matters, and to have a better relationship with science and society. I was really frustrated seeing science being misquoted in the news, so I started trying to figure out ways to do science communication. That led me to this whole process of developing workshops and a student group called Public Communication for Researchers. I was leaving the traditional science route. I have one foot in the science world and one foot in the writing world — the crossover has always been there. I think it’s a very Oberlin thing. It’s about how to do good in the world and change the world.

Can you talk a little bit about your writing process, either for this poem specifically or in general?

For me, poetry starts with keeping an idea notebook. I just started to go around the world and notice things and write them down, what Meghan Falley called “glimmers,” although I’m not sure if she created that term. Once you start having these, you can sit down and work. I would do some drafts, and then what was really the gift of finding poetry communities is I would meet with them every week to workshop. I did that for maybe two or three years after I took this workshop — just meeting and reading each others’ work and having some co-working time. I learned different things to look for in poetry to make it stronger. There became sort of a philosophy of poetry, of what I think makes something interesting. It’s balancing the ways you talk about abstract, emotional ideas, that we nicknamed “clouds” and “anchors,” things that are sort of specific and really down to what’s happening. And so I’m trying to find a good mix of those things.

One of the funny things about this poem in particular: it’s my second acceptance ever. Last year, I racked up 100 rejections — I made it a goal to get 100 rejections, and then I celebrated. I had a rejection celebration party. In fact, I even submitted a version of this poem to the same contest last year, and it didn’t make it out of round one. What do I make of that? I kept working on it. So I think it’s also about the power of revision, that I tweak things and make things a little bit sharper. I said, “Okay, this is just another opportunity to keep working on it.” It’s not magic. You just keep doing it.

What about Oberlin do you think shaped you the most?

I felt encouraged to explore things based on intellectual interest and not based on already being good at them. I think it’s really important to do things that you enjoy even when you’re not good at them. I learned to pay attention to what was pulling me. It was a very exploratory time that let me not be constrained but learn from different disciplines. I think that’s something that was really good for me and I’ve tried to carry with me; following your interests where they go, as opposed to stopping them short. That’s the thing that still sticks with me more than 10 years later.